The memorial pictured here commemorates the Quebec City riot of Easter weekend, 1918 [1]. It sits in St-Roch, a predominantly working-class neighborhood in Quebec City. It is right beside a bus shelter. In fact, part of the memorial (not pictured here, but directly to the right of the column) acts as a functional bench for those waiting for the bus.

On 1 April 1918, in this very area of St-Roch, soldiers from Ontario reacted to civilians whose opposition to conscription had turned violent. A lengthy text panel accompanies the stele. Named for Jean Provencher's 1974 play "Quebec, Printemps 1918", the text tells of the riot. If you click on the photo and zoom in, you can read the text. Alternatively, there is a Wikipedia page on the memorial that includes its full text.

The text tells that, for five days, citizens mounted active opposition to conscription. It tells that the federal government used anglophone soldiers from Ontario and the West to deal with the rioters. After reading the riot act in English only, it continues, the soldiers fired on the crowd, killing 4 and wounding 70 others. The panel explains the monument's symbolism, and lists the names of the 4 killed.

One of the friends I traveled to Quebec with this past weekend is writing his Master's thesis on the memorial. Chris is investigating the history it teaches, and the kind of memory it perpetuates. I am really looking forward to reading his work when it's finished, as, aside from what he told us in Quebec, I know absolutely nothing about the conscription crisis. I knew that there was some unfortunate thing called a conscription crisis, and that it featured some pretty angry Quebecois. This is likely, in part, a result of my failure to pay close enough attention in junior high Canadian history. But, wait: I wasn't a terrible student in junior high. I was even actively interested in history. I would like to think that, if the Quebec City riots had figured large in the curriculum, I would retain at least some memory of them.

I attended junior, and senior high school in Toronto from '93 - 2000. In those years, the story of the First World War that I learned of was about Vimy and Passchendale. It was about Canadian women on the home front. I just finished reading Jane Urquhart's The Stone Carvers; it's a fascinating and engaging read, and one that entirely corroborates the WWI story I learned. I'm quite sure my WWI story did not include any more than passing reference to opposition to conscription in Quebec. My WWI story certainly was clearly not heavily inspired by Provencher [2].

Another friend of mine, now doing PhD work in Canadian history, attended public school in Shawinigan in the mid- to late'90s. This likely sounds naive, but I was completely amazed to learn that his WWI story had not included the battlefields of the Western front. His was, it seems, more of a social history of Quebec, and a story of of tensions between local, provincial and federal politics and politicians of the time.

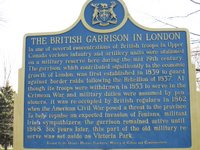

Standing in front of the Quebec, Printemps 1918 monument (and helping us to translate its text) Chris explained that there are huge inaccuracies in the story it tells. But who, in St-Roch, we wondered, would question its narrative? Further, if someone were to wonder at it, what would it take for him or her to research the history, and to challenge the narrative? We then started to wonder about the stories that monuments in Ontario had told us - stories that seemed so straightforward that we had never questioned them.

I'm not, in any way, trying to illustrate conspiracy, or propaganda. I don't know enough about the history of the conscription crisis in Canada, or about the ins-and-outs of our nation's different WWI narratives to do so. I just wanted to take a moment to reflect on the scope, and power of Canadian memories. Not until this past weekend did I appreciate just how disparate memories in Canada are, and will likely continue to be.

------------------------------------------------------------

[1] See the Newspaper Extract, "Five civilians shot by soldiers in Quebec City

April 2, 1918" on the McCord Museum's Keys to History online exhibit. I wrote a blog post a couple of months ago on the success of the McCord's online exhibits, and of the tagging and collecting functions that the My Folders function allows the museum's online visitor over digitized artefacts. I googled "quebec city 1918 riots", and the McCord's page, complete with a digitized image of La Presse's 2 April '18 page, was the fourth result listed. The page offers a short history of the riot, explaining its connection to the conscription crisis. While this page is useful, I will criticize the lack of navigation tools it offers me. I came at this artefact through a 'back door' - that is, by arriving at the precise artefact via my broad Google search. It seems that the artefact is, however, a part of someone's Folder of collected items. The Folder is unnamed, and I can't find a link to provide me with some context to understand who created this Folder.

[2] See Jean Provencher, Québec sous la loi des mesures de querre, 1918 (Trois-Rivières: Boréal-express, 1971). My friend who is working on this thesis told me that Provencher's interpretation remains the seminal Quebecois work on the conscription crisis.