On the afternoon of Sunday 19 November, there was a bright yellow parrot in the William's Coffee Pub on Richmond St. A dapper looking older gentleman brought the bird into the shop with him. Man and uncaged bird sat together at a booth for a moment, watching the world go by. Then the bird squawked, hopped down from the booth and toddled around on the floor. The man scooped it up, set it on the table, and went to the counter alone to get a coffee. The bird stayed still, guarding the booth.

The scene, of course, woke me out of the stupor that reading the aforementioned, remarkably uninteresting, Europe in the Sixteenth Century textbook had put me in. The bright yellow bird also startled others. One young couple headed to claim the booth and, when they saw the parrot, were visibly discombobulated. They looked at each other, at the parrot, and then around at other customers ( who, like I was, were watching & waiting for their reaction). I could almost hear their thoughts - are we nuts? Does anyone else see that big, crazy-looking bird? I don't even need to tell you how the after-church ladies' crowd reacted to the scene.

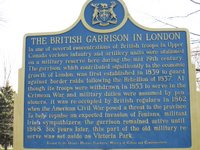

While all of this transpired to my immediate left, two hundred paces to my right, outside the coffee shop and in the middle of Victoria Park, stood one of those stoic iron historical plaques that we had been reading about for that week's Public History class. The plaque commemorates the British Garrison in London.

The crazy parrot-related confusion on my left and the staid, quiet plaque in peaceful Victoria Park on my right seemed to occupy two entirely incongruous realities. Our commemorative plaques, I reflected, could do with being a little more like bright yellow parrots. Without tearing down all of our country's classy-looking little iron beauties (an act that would not only be expensive and wasteful, but would likely anger many[1]), perhaps we can update some of them. Perhaps we can infuse them with a little bit of the surprise value that the vision of a tropical bird in a London coffee shop engenders.

The plaque in Victoria Park waits patiently for the passerby to approach it. It is silent, and passive. This is all fine and good, as I'd imagine most of us don't want to be harassed by a commemoration when all we're after is a good coffee on a Sunday afternoon.

But what if we made even some of our plaques active? [2] What if we designed some of them to interrupt our busy activities? We have the means to make the public history equivalent to that yummy smell that Saint Cinnamon pumps out of its store - the one that makes you stop and take notice of your surroundings when you're barreling through the mall, too occupied with your Christmas shopping to really take note of anything extraneous.

American artist Shimon Attie installed a project in Berlin's Scheunenviertel district in 1992 titled "The Writing on the Wall." It consisted of slides of Jewish life in the '20s and '30s, projected onto the façades of the same, or nearby addresses in the district. Attie had been trying to make transparent the process of change through time, and, in this case, the loss of a people from Berlin.[3] Another similar temporary installation in Berlin was designed so that passerby set off a sensor which activated a projection of a short fact, such as, at this intersection, on 23 April 1943, Gestapo assembled 23 young German Jewish women from this community for deportation to Ravensbruck.

In my view, five factors work to make such a commemoration powerful:

1. Its 'surprise factor' - it instantly animated an otherwise innocuous-looking space,

2. it's relationship to the pedestrian - it appeared only when he or she occupied the immediate area,

3. the fact that it was a temporary art installation,

4. the fact that the event it commemorated took place at the exact spot where the commemoration now stood, and

5. that the Holocaust has become iconic in Western cultural memory

Now, clearly, there aren't any sites in London, ON, at which violent acts that would later be identified as part of the Holocaust occurred. I believe that the first four qualities on the above list can, however, be integrated into ongoing commemoration projects in a London context. Furthermore, I remain inspired by Carling's suggestion (made in our last Public History class, and reiterated on her recent blog post) that the Museum of Jurassic Technology struck her as more of a permanent art installation than a museum. I think that if public historians can fully embrace planning that places public commemoration in the realm of (permanent or temporary) installation art, as well as in the realm of history, we could create some genuinely dynamic projects.

Imagine, for example, walking by a normal-looking storefront on Dundas, say, just east of Richmond, when suddenly you hear,

"Hey, you! Yeah, you. You in the purple sweater. Beatrice McPherson lived here in 1911. She was very poor, and she lost her few belongings in a fire that same year."

This noisy commemoration could also (assuming it was programmed somehow) offer conflicting viewpoints of how Ms. McPherson's residence met its fiery demise. Half of the time, it could repeat one popular rumor that gained currency after the fire: that ol' Bea set the fire herself in a suicide attempt. The other half of the time it could repeat another: that the shopkeeper below was the arsonist.

This Ol' Bea example is fabricated (I don't know if there was a Bea on Dundas in 1911, and, if there was, I sincerely hope she didn't suffer a devastating fire). Further, an active monument isn't an original concept. In previous research projects, I have run across countless examples of what many refer to as "countermonuments" - projects that seek to challenge monuments' traditional form - in Germany. I'm certain they exist elsewhere.

The aim, however, of our hypothetical London example would be to work against the relegating of history to quiet, passive and often cordoned-off spaces [4]. Unfortunately, I'm sure we could all imagine that even the noisiest, most aesthetically interesting memorial could quickly become 'invisible.' It could only be a matter of time before the pestering memorial could become completely ordinary to Londoners.

Ideally, then, Ol' Bea would only be a temporary installation. Better yet, it could be one in a series of related commemorative installations. There is, after all, nothing more historical than constant change [5]. If we could attach such noisy plaques to places in the city that are in flux, (such as construction sites), we could work to animate commemoration.

Of course, Ontarians can boast a wealth of existing memorials and commemorative plaques. I would never advocate abandoning traditional memorial forms. I simply think there is much room for creative additions to our current memorial landscape.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Paul Litt wrote of being reprimanded by an angry Torontonian who caught him in the act of replacing an old historical plaque in the city's Beaches area. "You are taking away our history", the elderly man had yelled. Litt's article charts the history of our historic plaques. Although he determines that many plaques are now artefacts in themselves, most Ontarians continue to see the merit in our provincial plaque program. See Litt,“Pliant Clio and Immutable Texts: The Historiography of a Historical Marking Program,” The Public Historian vol.19 no.4 (Fall 1997), pp.7-28.

[2] Patricia K. Wood's writing on historic sites that strive to re-animate the past led me to think about making commemoration noisy, and active. Wood criticizes, in particular, how living museums in Calgary physically relegate attempts at re-animating the past to suburban sites. If she so chooses, the Calgarian could entirely avoid living museums in the greater metropolitan area. Wood raises interesting questions: how can we make successful commemoration projects not only present in the city core, but also relevant to those who live, work, and travel there? How can we make sure that we integrate material commemoration of the past into our dynamic, and ever-growing cities? See Wood, “The Historic Site as a Cultural Text: A Geography of Heritage in Calgary, Alberta,” Material History Review (Fall 2000), pp.33-43

[3] See Eyestorm's 2003 article on Attie's work for some photographs of his installations.

[4] Again, Wood's critique of living museums in Calgary underscores the problem of keeping history in pristine, artificial areas outside of where 'real' people live, work and play.

[5] Ian McKay has written about the politics of public commemoration in Nova Scotia from 1935-64. His article tells that new kind of history for tourists' consumption in NS in that period was “profoundly anti-historical.” Instead of presenting change through time, McKay argued that bureaucrats and promoters sought to freeze a moment in time, for example, in an all-too-perfectly restored building. See McKay,“History and the Tourist Gaze: The Politics of Commemoration in Nova Scotia, 1935-1964,” Acadiensis vol.22 no.2 (1993), pp.102-38.

1 comment:

I really like this post, Lauren. I agree that museums and heritage sites seem like an unnatural constriction of history. History is messy. It spills away from an historic site in a way that plaques can't possible illustrate. I think we as historians are sometimes afraid of being too in-your-face with our craft, and it's this notion--combined with the omnipresent budgetary considerations--that has tended to check innovation. Imagine what we could do if we had the money to compete with Coca-Cola for billboards and the sides of buses?

PS. Have you noticed that there's never a "young Bea"? What's with that?

Post a Comment